Young Adult

Featured New Releases

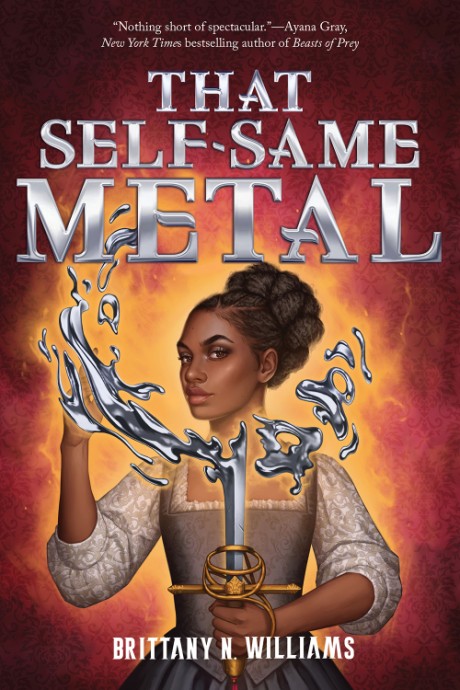

That Self-Same Metal (The Forge & Fracture Saga, Book 1)

$12.99

Thisstunning YA fantasy debut"seamlessly weaves together history, fantasy, culture, magic, and love" (New York Times bestselling author Daniel...

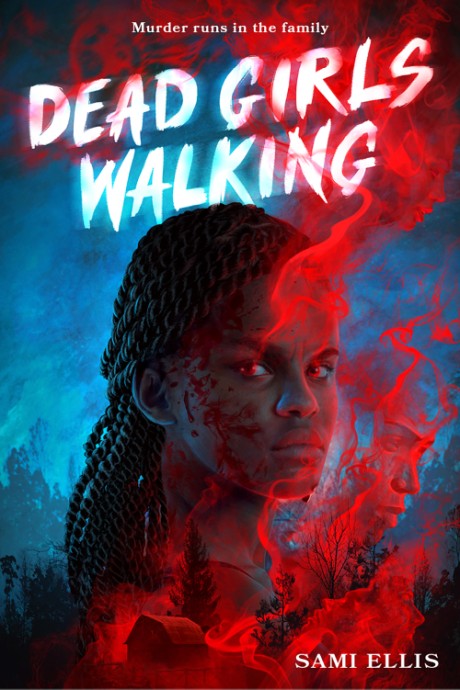

Dead Girls Walking

A Novel

$19.99

Sami Ellis's Dead Girls Walking is a shocking, spine-chilling YA horror slasher about a girl searching for her dead mother's body at the summer...

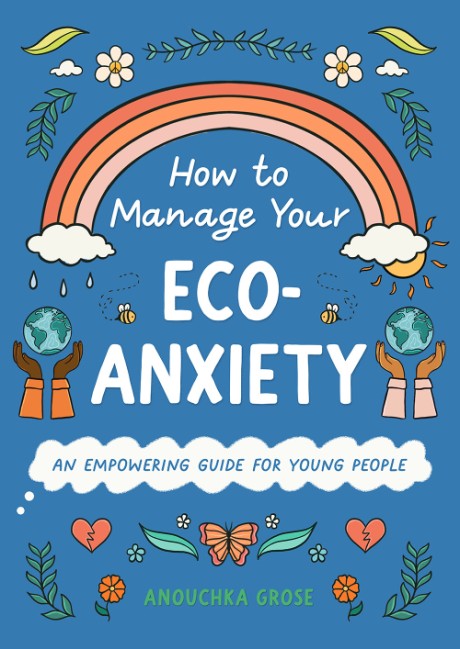

How to Manage Your Eco-Anxiety

An Empowering Guide for Young People

$18.99

How to Manage Your Eco-Anxiety is a timely book for teens that explores the relationship between mental health and the climate crisis . . . and...

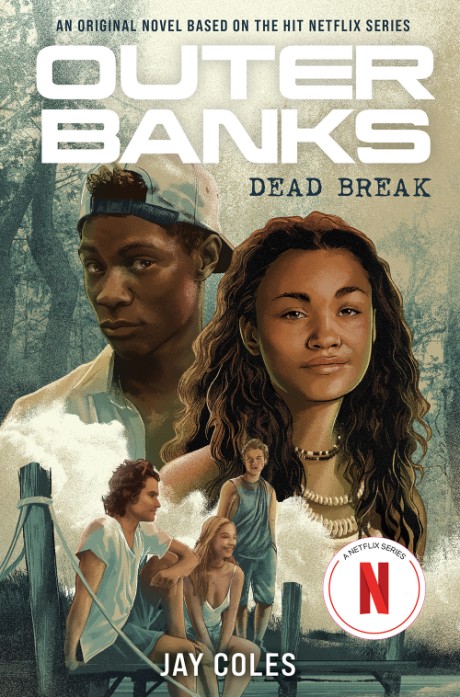

Outer Banks: Dead Break

$19.99

The Pogues hit the beach in another action–packed original YA novel based on the hit Netflix show, Outer Banks The waves are off the hook,...